Blog posts have moved to substack, Starting September 2023, all new posts are there. Of course, the archives remain here for your reading pleasure.

Author: Meryl

Toilets, Trains, and Tickets

For those of you who want more details on our trip, read on…

The rest of the world should model itself after Japan when it comes to toilets. Not only do they have wonderful gadgets, they are easy to find, plentiful and impeccably clean. Even toilets in bus and train stations and on the trains are sparkling. And public restrooms abound. They have buttons which heat the seats, and also that spray various jets of water on you if you want. But my favorite is the toilet that has a little spigot on top with fresh water that streams down when you flush so you can was your hands right away. The water goes into the toilet and adds to the flush. In any case, the best, cleanest toilets anywhere.

Throughout Japan, public transit is impressive, especailly the network of trains, crowned by the bullet trains, the Shinkansen. They go everywhere and are clean and orderly. When you get off, a bus or subway can take you most places, and a taxi waiting at the station is also an option. One thing I find odd, though. With multiple trains leaving frequently, you don’t seem to be able to buy an open ticket. For example, in NY, I can buy a Metro-Rail ticket to a destination and get on any train that’s convenient. In Japan, I have to choose a specific train. Even if I have a rail pass, or buy the ticket online, I need to get a paper ticket (or two) for that specific train. Lines to pick up tickets or to purchase them can be long. I don’t know what happens if you miss your specific train—so far I haven’t. In contrast, you can get on any bus or subway and pay with a Suica card, which you can have on your phone. Perhaps this has to do with reserved seating, which I always buy, but I think even for regular trains you need to choose before hand.

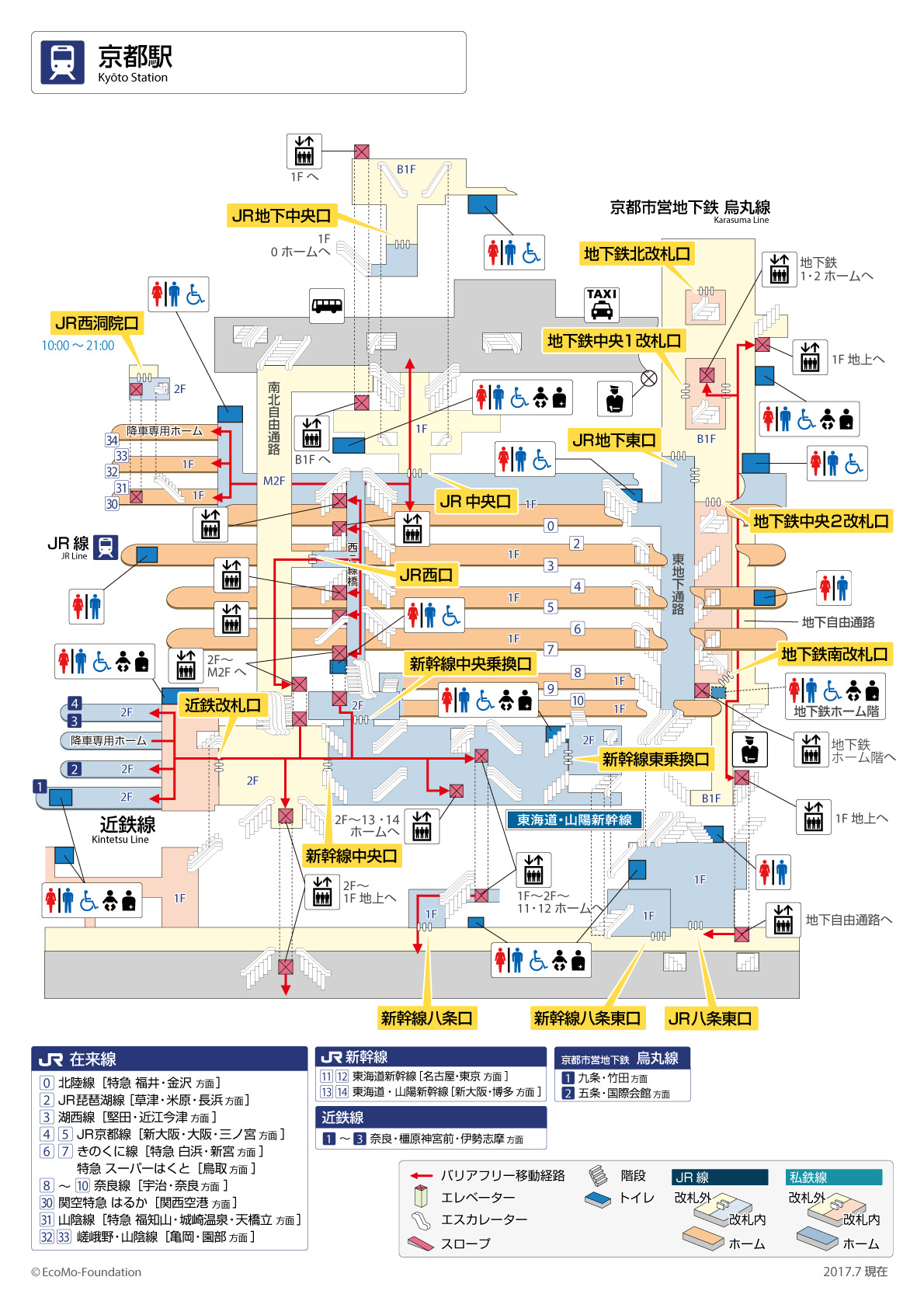

Train stations in Japanese cities (especially Kyoto) seem to me to have been designed by devotees of Kafka with a Capitalist twist. They are vast, labyrinthine, and filled with shops of all kinds from cheap trinkets to luxury items. I have yet to enter a station that wasn’t swarming with people rushing around. I spent over an in Kyoto trying to discover where we would catch a specific train from Kyoto to Kinosaki Onsen. I wasn’t successful, and came home to research and got a multipage guide to the station that included this map:

I discovered on my return to the station for our trip (an hour and a half early to be safe), that if I’d just entered from the central entrance, it would have been simple, with the Information booth in English and the trains right there.

Finally. from a Westerner’s point of view, the Japanese seem obsessed with tickets. Not only do you need multiple paper tickets for the train, often you need to get a flimsy paper ticket to buy something. The oddest example of this was in the tiny rural town of Tsumago. To buy soba, I pointed to the soba I wanted and was directed to a sort of vending machine and told to select that soba and add money. This produced a tiny ticket which I handed to the waitress which she handed to the cook, all standing right there. In some places, the ticket machine eliminates the waitress altogether, and you just hand your ticket in to get your food or drink. This isn’t omnipresent, but there do seem to be a lot of tickets.

Nonetheless, we are having a grand time, and appreciate the infinite patience, courtesy, and helpfulness of the average citizen as we bumble along.

The exemplary sentence

Despite the madness of war, we lived for a world that would be different.

Several years ago, I started posting favorite passages from prose that I am reading. I stole the title “The exemplary sentence,” from Mark Doty’s blog. It seems apt. This excerpt is from Tadeusz Borowski’s amazing book, This Way for the Gas Ladies and Gentlemen, which I first read in a Penguin paperback in the 70s and reread recently. The book is a collection of stories, the first stories that made the concentration camp experience seem real to me, to see how it simply became daily life for the participants, who to stay alive, necessarily became collaborators in their own imprisonment.

Here is one passage, slightly edited:

“Despite the madness of war, we lived for a world that would be different. For a better world to come when all this is over. And perhaps even our being here is a step toward that world. Do you really think that, without hope that such a world is possible, that the rights of man will be restored again, we could stand the concentration camp even for one day? It is that very hope that makes people go without a murmur to the gas chambers, keeps them from risking a revolt, paralyses them into numb inactivity…It is hope that compels man to hold on to one more day of life, because that day may be the day of liberation. Ah, and not even the hope for a different, better world but simply for life, a life of peace and rest…We were never taught how to give up hope, and this is why today we perish in gas chambers…

But still we continue to long for a world in which there is love between men, peace, and serene deliverance from our baser instincts…And yet, first of all, I should like to slaughter one or two men, just to throw off the concentration camp mentality, the effects of continual subservience, the effects of helplessly watching other being beaten and murdered, the effects of all this horror. I suspect though, that I will be marked for life. I do not know whether we shall survive, but I like to think that one day we shall have the courage to tell the world the whole truth and call it by its proper name.”

Borowski did survive, and the power of his work led Larry and I to find and translate his poetry years later, still the only selected poems of his in English. His survival was brief however, as like many survivors, he couldn’t stand that the world had not changed, that telling the truth made little difference. His life ended in suicide in 1951. Nonetheless, the work remains for those who care to read it.

Glitch with subscriptions…

I’ve discovered that none of the subscribers to this blog are getting post updates, so will pause until this glitch is fixed. Feel free to explore past posts in the meantime or subscribe to my Substack here.

Yannis Ritsos

This morning in my email I found this poem from the Paris Review. I loved the tone of it–quiet, haunting–no pretentions or duties.

Achilles After Dying

He was very tired—who cared about glory any longer? Enough was enough.

He had come to know enemies and friends—purported friends:

behind all the admiration and love they hid their self-interest,

their own suspicious dreams, those cunning innocents.

Now,

on the little island of Leuce, alone at last, peaceful, no pretensions,

no duties or tight armor, most of all without

the humble hypocrisy of heroism, hour after hour he can taste

the saltiness of evening, the stars, the silence, and that feeling—

mild and endless—of general futility, his only companions the wild goats.

But here too, even after dying,

he was pursued by new admirers—usurpers of his memory, these:

they set up altars and statues in his name, worshipped, left.

Sea-gulls alone stayed with him; now every morning they fly down to the shore,

wet their wings, fly back quickly to wash the floor of his temple

with gentle dance movements. In this way

a poetic idea circulates in the air (maybe his only justification)

and a condescending smile for everyone and everything crosses his lips

as he waits yet again for new pilgrims (and he knows how much he likes that)

with all their noise, their Thermos bottles, their eggs and phonographs,

as he now waits for Helen—yes, that same Helen for whose

fleshly and dreamy beauty

so many Achaeans and Trojans (he among them) were destroyed.

Yannis Ritsos—Translated from the Greek by Edmund Keeley

The exemplary sentence

I’ve been rereading Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth, my favorite of her books. As it opens, lovely, graceful, and without money of her own, Lily Barth needs to find a husband. She’s already 29, old for the job. But it’s hard for her. She attaches herself to Percy Gryce, a rich, eligible bachelor and draws him out on his favorite books, but he is so boring that just thinking about him later brings his droning voice clearly to mind, and she imagines the work of getting him to propose, summed up in this sentence.

“She had been bored all the afternoon by Percy Gryce–the mere thought seemed to raise an echo of his droning voice–but she could not ignore him on the morrow, she must follow up her success, must submit to more boredom, must be ready with fresh compliances and adaptabilities, and all on the bare chance that he might ultimately decide to do her the honor of boring her for life.”

Funny, but ultimately tragic for Lily, who can never quite bring herself to this wholly mercenary level. A wonderful read to finish up the summer.

Natalie Diaz

I know I’ve posted something from her book, Post-Colonial Love Poem, but I came across this one recently and love the sensuality in contrast to the landscape and car details.

If I Should Come Upon Your House Lonely in the West Texas Desert

I will swing my lasso of headlights

across your front porch,

let it drop like a rope of knotted light

at your feet.

While I put the car in park,

you will tie and tighten the loop

of light around your waist —

and I will be there with the other end

wrapped three times

around my hips horned with loneliness.

Reel me in across the glow-throbbing sea

of greenthread, bluestem prickly poppy,

the white inflorescence of yucca bells,

up the dust-lit stairs into your arms.

If you say to me, This is not your new house

but I am your new home,

I will enter the door of your throat,

hang my last lariat in the hallway,

build my altar of best books on your bedside table,

turn the lamp on and off, on and off, on and off.

I will lie down in you.

Eat my meals at the red table of your heart.

Each steaming bowl will be, Just right.

I will eat it all up,

break all your chairs to pieces.

If I try running off into the deep-purpling scrub brush,

you will remind me,

There is nowhere to go if you are already here,

and pat your hand on your lap lighted

by the topazion lux of the moon through the window,

say, Here, Love, sit here — when I do,

I will say, And here I still am.

Until then, Where are you? What is your address?

I am hurting. I am riding the night

on a full tank of gas and my headlights

are reaching out for something.

Natalie Diaz

originally appeared in The New York Times Magazine (April 1, 2021).

Keetje Kuipers

At the Minnesota Northwoods Writers’ Conference, Keetje Kuipers gave a knock-out reading. I bought her most recent book, All its Charms, and have been slowly reading through it. She has the amazing ability to make her poetry seem like easy, natural speech, while at the same time packing so much into each word. I especially love the tenderness in her work. Here’s a sample:

Landscape with Ocean and Nearly Dead Dog

Should I lay him on the slab at the vet’s? Let

somebody else do the work? Or back at home

in the yard, my coward’s hand on the syringe,

the last of the bird song in our ears? Now I find

one pink shell, one gray, watch my daughter

knee-deep in the waves as a child swims toward her

chewing flecks of styrofoam. It’s chicken, says the girl,

Eat it. And the ibis eyeing them, god-only-knows

in its gullet. What makes me want to take these fractures

home? The shale of blue plastic covered in stony

warts, starfish arm severed in the night, feelers

still tickling the air. I hold the dog’s head

in my lap, let him smell on my salted hands

every little thing we’re willing to give up.

Keetje Kuipers

Zagajewski

I just finished a slim, posthumous book of Adam Zagajewski’s poems. This little poem seems to me to capture exactly how it feels to long to write when you can’t:

Wind

We always forget what poetry is

(or maybe it happens only to me).

Poetry is a wind blowing from the gods, says

Cioran, citing the Aztecs.

But there are so many quiet, windless days.

The gods are napping then

or they’re preparing tax forms

for even loftier gods.

Oh may that wind return.

The wind blowing from the gods

let it come back, let that wind

awaken.

from The Life

translated by Clare Cavanagh

Raymond Carver

It’s rare that a writer can work well in both prose and poetry. Raymond Carver, best known for his short stories, has also written some intriguing short poems. Here’s one:

Sunday Night

Make use of the things around you.

This light rain

outside the window, for one.

This cigarette between my fingers,

these feet on the couch.

The faint sound of rock-and-roll,

the red Ferrari in my head.

The woman bumping

drunkenly around in the kitchen . . .

put it all in,

make use.

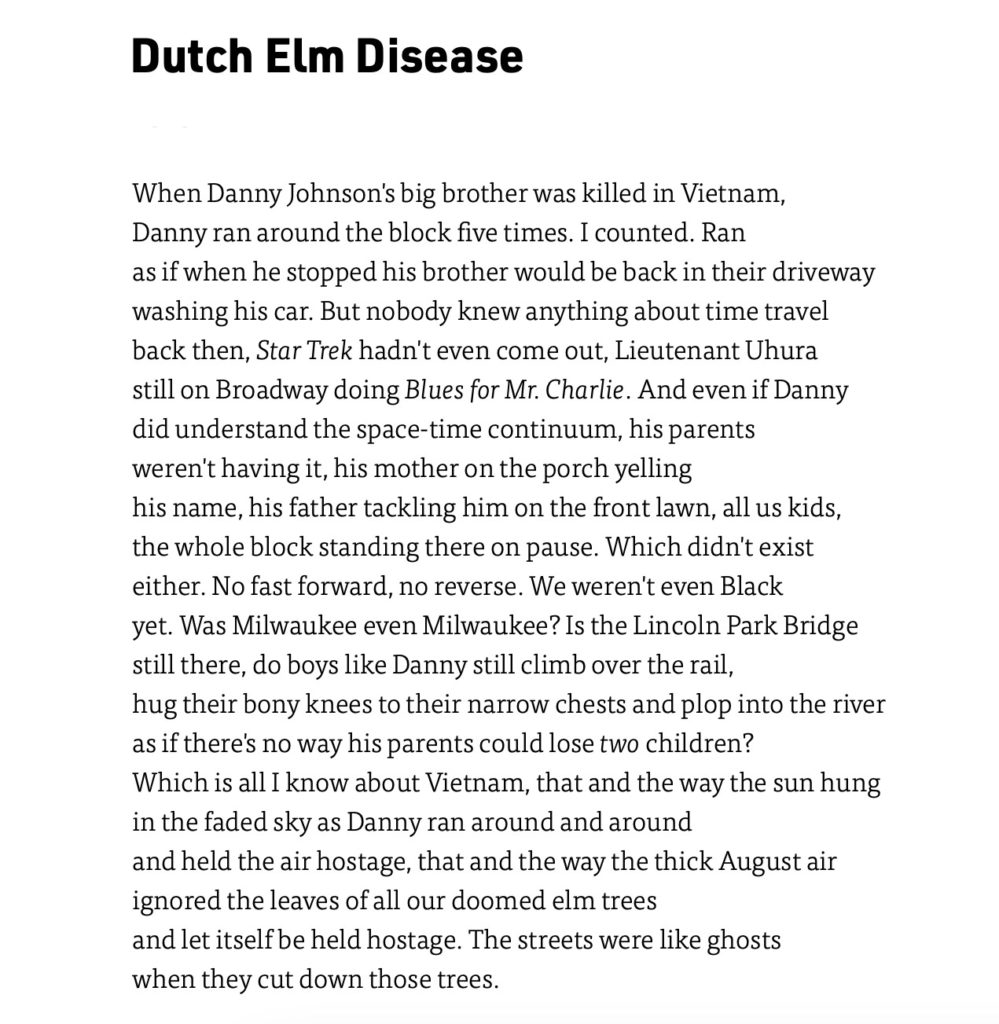

Elms

My high school had an ancient Dutch Elm on a hillside that was the logo of the school, so the blight that hit the elms was devastating, not just for itself, but for the school’s identity. The school recovered, of course, though the elm did not. So the title caught my attention when I saw Valencia Robin’s poem. But the quality of the poem was what made me post it here–it’s turn from and return to the absence of trees so imbued with sadness:

Valencia Robin

first printed in the New York Times and later iin Poetry Daily

Dreams

One of the deep pleasures of this blog is discovering poets I hadn’t encountered before whose work dazzles me. Today it’s Megan Nichols, whose poem I first read in Poetry Daily. My mother, a psychoanalyst, was a thoughtful interpreter of dreams. It was her forté–she could ask the right questions to eke out the often confusing meaning. So I found this poem especially vivid and moving as it cascades to the action of the ending.

Interpreting Dreams

If everyone in the dream is you

(and everyone in the dream is you)

then when you stand naked in the classroom,

you are the classmates, the teacher, and the flesh.

And when your mother drowns you in the tub

you are the mother, the child, and the bathwater.

And when all your teeth fall out at once, think

of yourself as not just the Chiclets clattering

to the tile, not just the empty mouth gaping, gums

softening like frozen yogurt melt. No, think

of yourself as the fall too, not the thing that will fall,

or the thing that has fallen, not the force behind

the falling, nor the thing that falls. You are the verb,

the act of, the motion as it moves.

from Threepenny Review