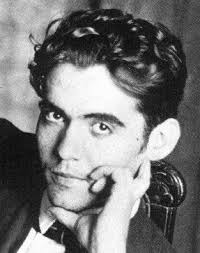

The first poet I read in translation who captured my imagination was Federico García Lorca (his full name is Federico del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús García Lorca, or Federico Sacred Heart of Jesus García Lorca!). I knew nothing about Franco, the Falangists, the Guardia Civil, or the Spanish Civil War, and less about surrealism in poetry. Perhaps I knew that they existed, but had no sense of their weight or meaning. But somehow the slim bilingual volume of his selected poems (thanks to Donald Allen) found its way to me when I was 18. The music of these poems led me to learn about him, his execution, and the forces at play in Europe of the thirties.

Here is the poem I loved most in that volume, without trying to make sense of it.

Ballad of the Sleepwalker

Ballad of the Sleepwalker

Green, how I want you green.

Green wind. Green branches.

The ship out on the sea

and the horse on the mountain.

With the shade around her waist

she dreams on her balcony,

green flesh, her hair green,

with eyes of cold silver.

Green, how I want you green.

Under the gypsy moon,

all things are watching her

and she cannot see them.

Green, how I want you green.

Great stars of frost

appear with the fish of shadow

that opens the road of dawn.

The fig tree rubs its wind

with the sandpaper of its branches,

and the forest, cunning cat,

bristles its brittle fibers.

But who will come? And from where?

She is still on her balcony

green flesh, her hair green,

dreaming in the bitter sea.

–My friend, I want to trade

my horse for her house,

my saddle for her mirror,

my knife for her blanket.

My friend, I come bleeding

from the gates of Cabra.

–If it were possible, my boy,

I’d help you fix that trade.

But now I am not I,

nor is my house now my house.

–My friend, I want to die

decently in my bed.

Of iron, if that’s possible,

with blankets of fine chambray.

Don’t you see the wound I have

from my chest up to my throat?

–Your white shirt has grown

thirsty dark brown roses.

Your blood oozes and flees a

round the corners of your sash.

But now I am not I,

nor is my house now my house.

–Let me climb up, at least,

up to the high balconies;

Let me climb up! Let me,

up to the green balconies.

Railings of the moon

through which the water rumbles.

Now the two friends climb up,

up to the high balconies.

Leaving a trail of blood.

Leaving a trail of teardrops.

Tin bell vines

were trembling on the roofs.

A thousand crystal tambourines

struck at the dawn light.

Green, how I want you green,

green wind, green branches.

The two friends climbed up.

The stiff wind left

in their mouths, a strange taste

of bile, of mint, and of basil

My friend, where is she–tell me–

where is your bitter girl?

How many times she waited for you!

How many times would she wait for you,

cool face, black hair,

on this green balcony!

Over the mouth of the cistern

the gypsy girl was swinging,

green flesh, her hair green,

with eyes of cold silver.

An icicle of moon

holds her up above the water.

The night became intimate

like a little plaza.

Drunken “Guardias Civiles”

were pounding on the door.

Green, how I want you green.

Green wind. Green branches.

The ship out on the sea.

And the horse on the mountain.

For those of you who like to see the original language, here it is. I don’t think you have to know Spanish to enjoy it:

Romance Sonámbulo

Verde que te quiero verde.

Verde viento. Verdes ramas.

El barco sobre la mar

y el caballo en la montaña.

Con la sombra en la cintura

ella sueña en su baranda,

verde carne, pelo verde,

con ojos de fría plata.

Verde que te quiero verde.

Bajo la luna gitana,

las cosas la están mirando

y ella no puede mirarlas.

Verde que te quiero verde.

Grandes estrellas de escarcha

vienen con el pez de sombra

que abre el camino del alba.

La higuera frota su viento

con la lija de sus ramas,

y el monte, gato garduño,

eriza sus pitas agrias.

¿Pero quién vendra? ¿Y por dónde…?

Ella sigue en su baranda,

Verde carne, pelo verde,

soñando en la mar amarga.

–Compadre, quiero cambiar

mi caballo por su casa,

mi montura por su espejo,

mi cuchillo per su manta.

Compadre, vengo sangrando,

desde los puertos de Cabra.

–Si yo pudiera, mocito,

este trato se cerraba.

Pero yo ya no soy yo,

ni mi casa es ya mi casa.

–Compadre, quiero morir

decentemente en mi cama.

De acero, si puede ser,

con las sábanas de holanda.

¿No ves la herida que tengo

desde el pecho a la garganta?

–Trescientas rosas morenas

lleva tu pechera blanca.

Tu sangre rezuma y huele

alrededor de tu faja.

Pero yo ya no soy yo,

ni mi casa es ya mi casa.

–Dejadme subir al menos

hasta las altas barandas;

¡dejadme subir!, dejadme,

hasta las verdes barandas.

Barandales de la luna

por donde retumba el agua.

Ya suben los dos compadres

hacia las altas barandas.

Dejando un rastro de sangre.

Dejando un rastro de lágrimas.

Temblaban en los tejados

farolillos de hojalata.

Mil panderos de cristal

herían la madrugada.

Verde que te quiero verde,

verde viento, verdes ramas.

Los dos compadres subieron.

El largo viento dejaba

en la boca un raro gusto

de hiel, de menta y de albahaca.

¡Compadre! ¿Donde está, díme?

¿Donde está tu niña amarga?

¡Cuántas veces te esperó!

¡Cuántas veces te esperara,

cara fresca, negro pelo,

en esta verde baranda!

Sobre el rostro del aljibe

se mecía la gitana.

Verde carne, pelo verde,

con ojos de fría plata.

Un carámbano de luna

la sostiene sobre el agua.

La noche se puso íntima

como una pequeña plaza.

Guardias civiles borrachos

en la puerta golpeaban.

Verde que te quiero verde.

Verde viento. Verdes ramas.

El barco sobre la mar.

Y el caballo en la montaña.

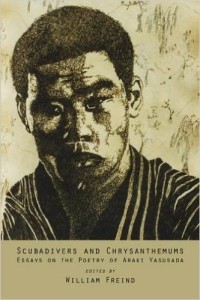

In the discussion, an older, more complex work came up: the two volumes, one of letters, one of poetry, allegedly by a Japanese survivor of Hiroshima, Akiri Yasusada, whose family was devastated by the blast.

In the discussion, an older, more complex work came up: the two volumes, one of letters, one of poetry, allegedly by a Japanese survivor of Hiroshima, Akiri Yasusada, whose family was devastated by the blast.