Blog posts have moved to substack, Starting September 2023, all new posts are there. Of course, the archives remain here for your reading pleasure.

Category: Uncategorized

Toilets, Trains, and Tickets

For those of you who want more details on our trip, read on…

The rest of the world should model itself after Japan when it comes to toilets. Not only do they have wonderful gadgets, they are easy to find, plentiful and impeccably clean. Even toilets in bus and train stations and on the trains are sparkling. And public restrooms abound. They have buttons which heat the seats, and also that spray various jets of water on you if you want. But my favorite is the toilet that has a little spigot on top with fresh water that streams down when you flush so you can was your hands right away. The water goes into the toilet and adds to the flush. In any case, the best, cleanest toilets anywhere.

Throughout Japan, public transit is impressive, especailly the network of trains, crowned by the bullet trains, the Shinkansen. They go everywhere and are clean and orderly. When you get off, a bus or subway can take you most places, and a taxi waiting at the station is also an option. One thing I find odd, though. With multiple trains leaving frequently, you don’t seem to be able to buy an open ticket. For example, in NY, I can buy a Metro-Rail ticket to a destination and get on any train that’s convenient. In Japan, I have to choose a specific train. Even if I have a rail pass, or buy the ticket online, I need to get a paper ticket (or two) for that specific train. Lines to pick up tickets or to purchase them can be long. I don’t know what happens if you miss your specific train—so far I haven’t. In contrast, you can get on any bus or subway and pay with a Suica card, which you can have on your phone. Perhaps this has to do with reserved seating, which I always buy, but I think even for regular trains you need to choose before hand.

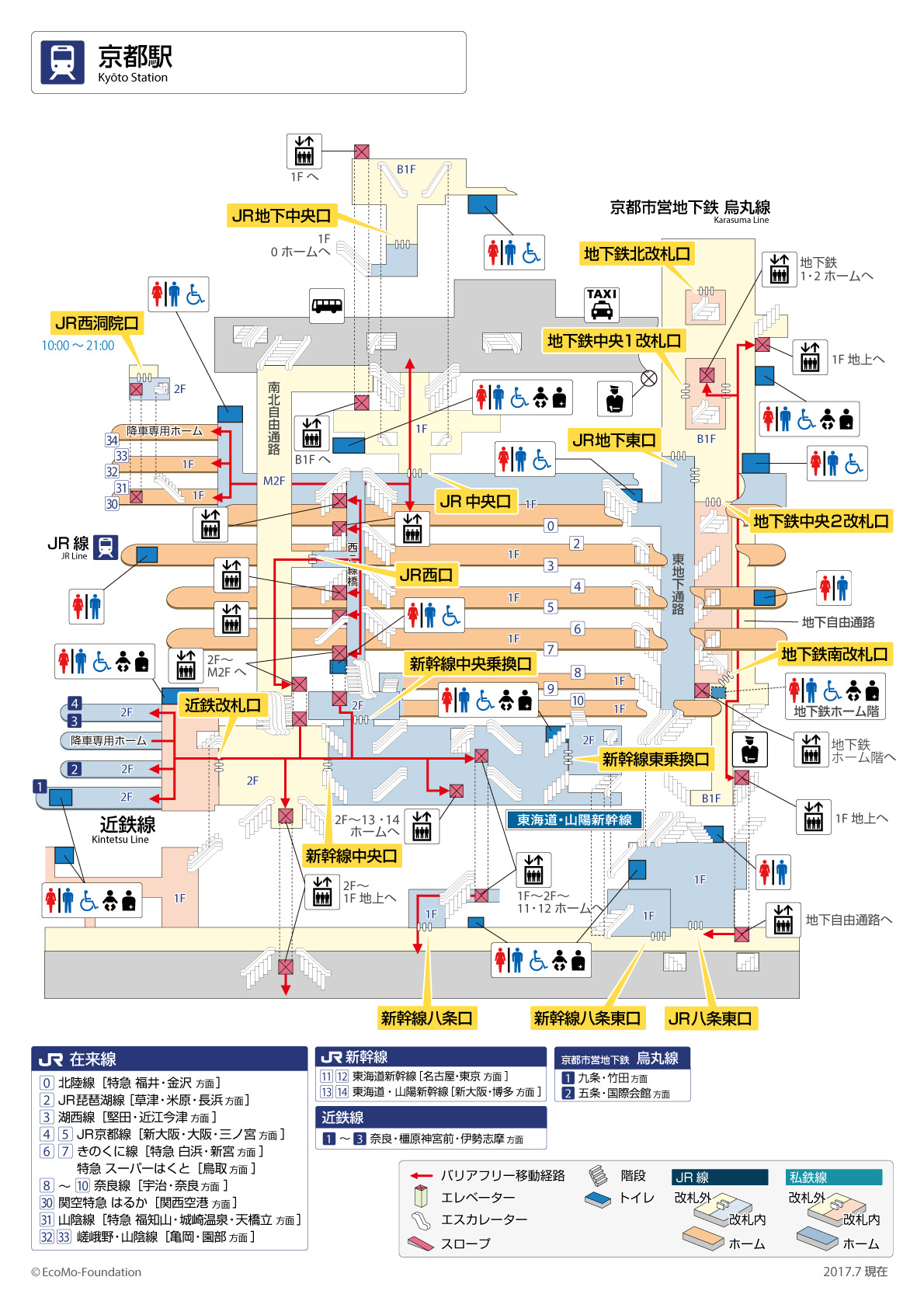

Train stations in Japanese cities (especially Kyoto) seem to me to have been designed by devotees of Kafka with a Capitalist twist. They are vast, labyrinthine, and filled with shops of all kinds from cheap trinkets to luxury items. I have yet to enter a station that wasn’t swarming with people rushing around. I spent over an in Kyoto trying to discover where we would catch a specific train from Kyoto to Kinosaki Onsen. I wasn’t successful, and came home to research and got a multipage guide to the station that included this map:

I discovered on my return to the station for our trip (an hour and a half early to be safe), that if I’d just entered from the central entrance, it would have been simple, with the Information booth in English and the trains right there.

Finally. from a Westerner’s point of view, the Japanese seem obsessed with tickets. Not only do you need multiple paper tickets for the train, often you need to get a flimsy paper ticket to buy something. The oddest example of this was in the tiny rural town of Tsumago. To buy soba, I pointed to the soba I wanted and was directed to a sort of vending machine and told to select that soba and add money. This produced a tiny ticket which I handed to the waitress which she handed to the cook, all standing right there. In some places, the ticket machine eliminates the waitress altogether, and you just hand your ticket in to get your food or drink. This isn’t omnipresent, but there do seem to be a lot of tickets.

Nonetheless, we are having a grand time, and appreciate the infinite patience, courtesy, and helpfulness of the average citizen as we bumble along.

The exemplary sentence

Despite the madness of war, we lived for a world that would be different.

Several years ago, I started posting favorite passages from prose that I am reading. I stole the title “The exemplary sentence,” from Mark Doty’s blog. It seems apt. This excerpt is from Tadeusz Borowski’s amazing book, This Way for the Gas Ladies and Gentlemen, which I first read in a Penguin paperback in the 70s and reread recently. The book is a collection of stories, the first stories that made the concentration camp experience seem real to me, to see how it simply became daily life for the participants, who to stay alive, necessarily became collaborators in their own imprisonment.

Here is one passage, slightly edited:

“Despite the madness of war, we lived for a world that would be different. For a better world to come when all this is over. And perhaps even our being here is a step toward that world. Do you really think that, without hope that such a world is possible, that the rights of man will be restored again, we could stand the concentration camp even for one day? It is that very hope that makes people go without a murmur to the gas chambers, keeps them from risking a revolt, paralyses them into numb inactivity…It is hope that compels man to hold on to one more day of life, because that day may be the day of liberation. Ah, and not even the hope for a different, better world but simply for life, a life of peace and rest…We were never taught how to give up hope, and this is why today we perish in gas chambers…

But still we continue to long for a world in which there is love between men, peace, and serene deliverance from our baser instincts…And yet, first of all, I should like to slaughter one or two men, just to throw off the concentration camp mentality, the effects of continual subservience, the effects of helplessly watching other being beaten and murdered, the effects of all this horror. I suspect though, that I will be marked for life. I do not know whether we shall survive, but I like to think that one day we shall have the courage to tell the world the whole truth and call it by its proper name.”

Borowski did survive, and the power of his work led Larry and I to find and translate his poetry years later, still the only selected poems of his in English. His survival was brief however, as like many survivors, he couldn’t stand that the world had not changed, that telling the truth made little difference. His life ended in suicide in 1951. Nonetheless, the work remains for those who care to read it.

Glitch with subscriptions…

I’ve discovered that none of the subscribers to this blog are getting post updates, so will pause until this glitch is fixed. Feel free to explore past posts in the meantime or subscribe to my Substack here.

Poetry and Science

This poem reminds me how poems can arise from any experience. I especially love the references to Keats and how the poem contains so much.

Anatomy Exam

Today at the college library the students check out arms

and legs—towering models of muscles and veins

perched on a stand like a hat rack. The exam

just two weeks before Cadaver Day, when they will arrive

pale-faced and woozy in my lit class. I will read them

Keats and they will think of the vastus medialis

and the rectus femoris, and how they looked not strong

and red as on the model but brown and shriveled,

spoiled like old meat. They will think of the sound of their

blade slicing into a corpse’s leg, of the tibial nerve running

long and taut like a highway straight down to the ankle,

of the precarity of their bodies made only of body.

I will tell them that Keats trained as a surgeon before

donating his body to poetry, how he died just a few years

older than them. But their mind will stay lost in the length

of the leg on the table: how the toes wriggled with a tug

on the ribboned tendons, how the toes had nails, how

the nails once grew, how an old woman with a name

once bent to trim them over a toilet bowl. And now

after all to feel so temporary, to hear finally the words

within the words uttered sacred by the preacher,

the teacher, the nurse. Beauty is truth and truth is beauty,

but a body on a table is made of parts with names

that must be known as certainly as Adam knew the names

of the animals, or at least as I know my own—name of

the body I live in, a body I’ve long thought of offering,

so I can teach again in death. But that is not for today.

Today is for hopeful plastic models that snap together

like toys. Today they color the arteries red and the veins blue,

dreaming of their scrubs and their stethoscopes,

strangers to Keats and the plague they’ll soon grapple.

Today the answer is not: Someone once kissed this spot, so tender

behind the knee, but, Gracilis, plantaris, extensor hallucis longus.

Alyse Knorr

first published in The Southern Review

A Celebration

I love the mysteriousness of this poem, the juxtapositions, the quiet ominousness, and the way it moves the way the mind moves. So lucky that translation brings this poem to us.

A Celebration

The thread of the story fell to the ground, so I went down on my hands and knees to hunt for it. This was at one of those patriotic celebrations, and all I saw were imported shoes and jackboots.

. Once, on the train, an Afghan woman who had never seen Afghanistan said to me, “Triumph is possible.” Is that a prophecy? I wanted to ask. But my Persian was straight from a beginner’s textbook and she looked, while listening to me, as though she were picking through a wardrobe whose owner had died in a fire.

. Let’s assume the people arrived en masse at the square. Let’s assume the people is not a dirty word and that we know the meaning of the phrase en masse. Then how did all these police dogs get here? Who fitted them with parti-colored masks? More important, where is the line between flags and lingerie, anthems and anathemas, God and his creations—the ones who pay taxes and walk on earth?

. Celebration. As if I’d never said the word before. As if it came from a Greek lexicon in which the victorious Spartans march home with Persian blood still wet on their spears and shields.

. Perhaps there was no train, no prophecy, no Afghan woman sitting across from me for two hours. At times, for his own amusement, God leads our memories astray. What I can say is that from down here, among the shoes and jackboots, I’ll never know for certain who triumphed over whom.

Tired of poetry

Sometimes I feel overwhelmed by the unread poetry books on every surface in my house. Then I can appreciate Alice’s sentiment:

For Juneteenth

I heard Danez Smith read before the Pandemic. His energy from the slam tradition is ebullient, and his poems are powerful. Here is one for this holiday. As usual, I especially like the ending.

I heard Danez Smith read before the Pandemic. His energy from the slam tradition is ebullient, and his poems are powerful. Here is one for this holiday. As usual, I especially like the ending.

C.R.E.A.M.

after Morgan Parker, after Wu-Tang

in the morning I think about money

green horned lord of my waking

forest in which I stumbled toward no salvation

prison made of emerald & pennies

in my wallet I keep anxiety & a condom

I used to sell my body but now my blood spoiled

All my favorite songs tell me to get money

I’d rob a bank but I’m a poet

I’m so broke I’m a genius

If I was white, I’d take pictures of other pictures & sell them

I come from sharecroppers who come from slaves who do not come from kings

sometimes I pay the weed man before I pay the light bill

sometimes is a synonym for often

I just want a grant or a fellowship or a rich white husband & I’ll be straight

I feel most colored when I’m looking at my bank account

I feel most colored when I scream ball so hard motherfuckas wanna find me

I spent one summer stealing from ragstock

If I went to jail I’d live rent-free but there is no way to avoid making white people richer

A prison is a plantation made of stone & steel

Being locked up for selling drugs = Being locked up for trying to eat

a bald fade cost 20 bones now a days

what’s a blacker tax than blackness?

what cost more than being American and poor?

here is where I say reparations.

here is where I say got 20 bucks I can borrow?

student loans are like slavery but not but with vacation days but not but police

I don’t know what it says about me when white institutions give me money

how much is the power ball this week?

I’mma print my own money and be my own god and live forever in a green frame

my grandmamma is great at saving money

before my grandfather passed he showed me where he hid his money & his gun

my aunt can’t hold on to a dollar, a job, her brain

I love how easy it is to be bad with money

don’t ask me about my taxes

the b in debt is a silent black boy trapped

The Exemplary Sentence

It’s been awhile since I published a prose piece. This snippet is from Wisława Szymborska’s How to Start Writing (and When to Stop) and first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter. It comes from the advice she gave—anonymously—for many years in “Literary Mailbox,” a regular column in the Polish journal Literary Life, and is translated by the indefatigable Clare Cavanagh, who has brought us most of the wonderful Polish poetry and prose that we have in English.

It’s been awhile since I published a prose piece. This snippet is from Wisława Szymborska’s How to Start Writing (and When to Stop) and first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter. It comes from the advice she gave—anonymously—for many years in “Literary Mailbox,” a regular column in the Polish journal Literary Life, and is translated by the indefatigable Clare Cavanagh, who has brought us most of the wonderful Polish poetry and prose that we have in English.

“The same old complaint about ‘youth.’ This time we’re supposed to forgive the author since he still hasn’t been anywhere, experienced anything worth mentioning, or read everything that he should. Such confessions betray the belief (adolescent, hence a bit simplistic) that external circumstances alone make the writer. That his creative quality derives from the quantity of his life adventures. In fact, the writer develops internally, within his own heart and mind: through an innate (we repeat, innate) propensity for thought, acute sensitivity to minor matters, astonishment at what others see as ordinary. Trips abroad? We sincerely hope you’ll take them, they sometimes come in handy. But before you head off to Capri, we suggest a trip to Lesser Wółka. If you come back with nothing to write about, then no azure grottoes will save you.”

When we were in Krakow a few years ago (sadly we missed Lesser Wółka), there was a museum show called Szymborska’s Desk, which had a facsimile of her writing room with many artifacts. I found it truly charming, and was only sorry I never got to meet the writer herself. Here is her yellow typewriter from that show.

When we were in Krakow a few years ago (sadly we missed Lesser Wółka), there was a museum show called Szymborska’s Desk, which had a facsimile of her writing room with many artifacts. I found it truly charming, and was only sorry I never got to meet the writer herself. Here is her yellow typewriter from that show.

No poem this week

Gone camping!

Starting fresh

With hope for a better new year, a poem that seems appropriate–of course, right now no flying to Rome or Greece. Still…

The New Experience

I was ready for a new experience.

All the old ones had burned out.

They lay in little ashy heaps along the roadside

And blew in drifts across the fairgrounds and fields.

From a distance some appeared to be smoldering

But when I approached with my hat in my hands

They let out small puffs of smoke and expired.

Through the windows of houses I saw lives lit up

With the otherworldly glow of TV

And these were smoking a little bit too.

I flew to Rome. I flew to Greece.

I sat on a rock in the shade of the Acropolis

And conjured dusky columns in the clouds.

I watched waves lap the crumbling coast.

I heard wind strip the woods.

I saw the last living snow leopard

Pacing in the dirt. Experience taught me

That nothing worth doing is worth doing

For the sake of experience alone.

I bit into an apple that tasted sweetly of time.

The sun came out. It was the old sun

With only a few billion years left to shine.

from The Irrationalist

So many husbands on Monday

It’s always a delight to discover a new poet. Here is a poem by Aimee Nezhukumatathil. I love the whole neighborhood of past loves. Don’t we all have that, even if they are long past? And that last line is killer:

It’s always a delight to discover a new poet. Here is a poem by Aimee Nezhukumatathil. I love the whole neighborhood of past loves. Don’t we all have that, even if they are long past? And that last line is killer: