I will be rafting next week, so this post is for next Monday. I saw this lovely lobster poem in Sean the Sharpener’s morning missive–poems about crustaceans. I had previously posted Nemerov’s wonderful lobster poem. Kay had an “s” on flamenco, which I ruthlessly and presumptuously removed. I hope she doesn’t mind. Also in Sean’s post was a link to a Robert Johnson tune,

I enjoy Robert Johnson’s music, but to me every tune of his seems the same, which I mentioned to Larry. “But that’s because when Alan Lomax recorded him, he only wanted him to play the blues,” said Larry. “He played all kinds of music, popular tunes, dance tunes, whatever people wanted, but that’s the only recording of him we have.”

He went on to tell me that when Lomax’s recording came out, in 1961 it had a huge influence on the Rolling Stones and other rock groups in England, which then came back across to influence American rock and roll. Robert Johnson was almost unknown when he died, and for decades after, but when that record came out his influence was huge.

“Too bad he’d already sold his soul at the crossroads and died,” I commented, referring to a legend about Johnson.

“Well, at least he attained an aristocratic place in hell,” was Larry’s quick response.

All this to bring you this little poem:

Crustacean Island

There could be an island paradise

where crustaceans prevail.

Click, click, go the lobsters

with their china mits and

articulated tails.

It would not be sad like whales

with their immense and patient sieving

and the sobering modesty

of their general way of living.

It would be an island blessed

with only cold-blooded residents

and no human angle.

It would echo with a thousand castanets

and no flamenco.

Kay Ryan

from Elephant Rocks

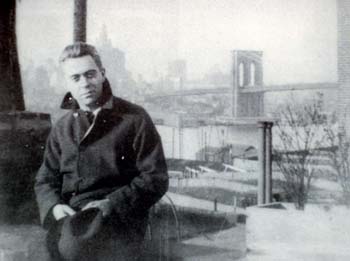

Hart Crane was one of my favorite poets when I was a teenager. I used to wander around reciting his musical poems aloud. His most famous poem is “To Brooklyn Bridge.” Now he seems almost unnoticed, so I thought I’d post one of his that I remember. I especially love the last four lines.

Hart Crane was one of my favorite poets when I was a teenager. I used to wander around reciting his musical poems aloud. His most famous poem is “To Brooklyn Bridge.” Now he seems almost unnoticed, so I thought I’d post one of his that I remember. I especially love the last four lines.