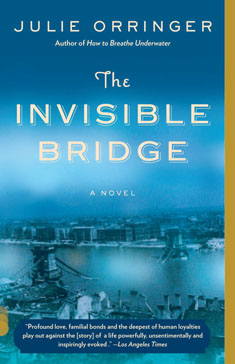

Last night we went down to Stanford to hear Julie Orringer read from her novel The Invisible Bridge. http://julieorringer.com/ is her website. I loved her book of stories, how to breathe underwater, when it appeared several years ago, and bought The Invisible Bridge as soon as it came out. It’s a marvelous novel, rich, compelling, painful. It’s the story of a Hungarian Jewish family starting in the 1930s and moving through World War II.

The genius of the book is that you become invested in the lives of the characters before the war, during “normal” life. When Hitler and Hungary’s fate make terrible choices necessary for the characters, it brings those events to life—so much so that you want to change history, to stop its crushing, implacable march. It makes you feel the impact of the war in a visceral way.

The genius of the book is that you become invested in the lives of the characters before the war, during “normal” life. When Hitler and Hungary’s fate make terrible choices necessary for the characters, it brings those events to life—so much so that you want to change history, to stop its crushing, implacable march. It makes you feel the impact of the war in a visceral way.

Here in the US, we don’t hear much about Hungary, a tiny country that tried to fight with the Germans against the Russians without buying into Hitler’s crusade against the Jews. It didn’t work, of course. But there was nobility in the struggle—a sort of old world dignity. I also recommend Sándor Márai’s Memoir of Hungary 1944-1948, a moving non-fiction account of the same period. I wrote this poem after reading his memoir:

Sándor Márai in Exile

Deprived of your native language,

of paprikash cooked in cramped kitchens,

of the scent of elder flowers in early June,

you don’t meet people you know on the street, or stop

in familiar shops that sell just what you need.

You don’t sit with friends

at the café with a newspaper filled

with gossip about people you know.

After your home was destroyed,

you said language was your true home.

But so few speak the Magyar tongue.

Even your name sounds unfamiliar here.

Who will read your forty-six books?

your scrupulous observations of

the German soldiers who set up radios

in your parlor? the Russians

who used it for their motorpool?

You saved your hatred for

your countrymen, newly minted

Soviets, returned from Moscow.

Their lethal mix of terror

and preferment snuffed

what little there was left of Hungary

and drove you out.

It’s lonely in the sun

of San Diego. Your bones crave cold light,

need winter in Krisztinaváros

before the siege,

the irreplaceable stones of Castle Hill.

Your mouth is parched

for the barbed sweetness of accented vowels,

the braided bread of consonants,

the bullets

of your spoken tongue.

Meryl Natchez