In the rarified intellectual world of boarding school, I arrived as a naïf in 10th grade. I was lucky to make a friend who later became a translator of Octavio Paz. He was always willing to explain a poem or a line to me. I remember clearly asking him to explain several passages of Prufrock when I first read it. What did it mean to “prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet”? And his answer—”That one’s so easy—it means to put on the mask you wear in public.”

He had a scathing wit, and for a few years after high school he was the secretary for our classes alumni notes section. He kept in touch with many alums, and his descriptions were not always kind. They were always fun to read, though. Unfortunately, the more sensitive of my classmates were offended, and he was asked to resign, which he did.

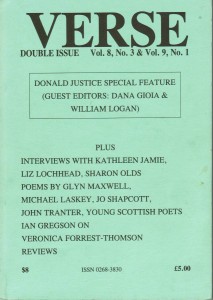

All of which brings me to the criticism of William Logan, whom I’ve mentioned briefly before. Most poetry criticism reads like a sanitized version of alumni notes—bland, kind, praising small achievements. The world of poetry is a small and cozy one, and few want to risk alienating their peers. But in the midst of this vapid sea of faint praise, there is an island of acerbic wit called William Logan. Though he writes and publishes verse, he seems to have no qualms about pricking the pretensions of the most lauded poets, and the poetry establishment itself. Here’s an excerpt from his 2009 review of Billy Collins’ book, Ballistics:

All of which brings me to the criticism of William Logan, whom I’ve mentioned briefly before. Most poetry criticism reads like a sanitized version of alumni notes—bland, kind, praising small achievements. The world of poetry is a small and cozy one, and few want to risk alienating their peers. But in the midst of this vapid sea of faint praise, there is an island of acerbic wit called William Logan. Though he writes and publishes verse, he seems to have no qualms about pricking the pretensions of the most lauded poets, and the poetry establishment itself. Here’s an excerpt from his 2009 review of Billy Collins’ book, Ballistics:

“When comedians stop being funny, they must invent themselves anew or retire for good. A number of poems here mention divorce in a roundabout way… Indeed, the most hilarious poem in the book is titled “Divorce,” and it’s also the shortest:

Once, two spoons in bed,

now tinned forks

across a granite table

and the knives they have hired.

If Collins can become the bitter philosopher of such lines, there’s hope yet. Otherwise, Poetry must do what Poetry does when a poet runs out of gas, or screws the pooch, or jumps the shark—give him a Pulitzer and show him the door.”[1]

Lucille Clifton used to say “Poetry is a house of many rooms,” meaning that there is room for a wide variety of style and form. But unlike a house, whose builders need to demonstrate a minimal level of carpentry skill for the house to stand, anyone at all can claim to be a poet, whether skilled or not. Here’s where knowledgeable critics help. William Logan, Dana Gioia, and Robert Hass have each written some wonderful prose about poetry and are all worth reading. Dana Gioia’s essay “The Successful Career of Robert Bly” in Can Poetry Matter? is one of my favorites of his work. Robert Hass’s collections of newspaper columns, Now and Then, and Poet’s Choice are both worth owning, and if you like these, you might want to go on to the more difficult Twentieth Century Pleasures. But no one makes me laugh as reliably as William Logan, and that’s worth a lot in this world of woe.

Lucille Clifton used to say “Poetry is a house of many rooms,” meaning that there is room for a wide variety of style and form. But unlike a house, whose builders need to demonstrate a minimal level of carpentry skill for the house to stand, anyone at all can claim to be a poet, whether skilled or not. Here’s where knowledgeable critics help. William Logan, Dana Gioia, and Robert Hass have each written some wonderful prose about poetry and are all worth reading. Dana Gioia’s essay “The Successful Career of Robert Bly” in Can Poetry Matter? is one of my favorites of his work. Robert Hass’s collections of newspaper columns, Now and Then, and Poet’s Choice are both worth owning, and if you like these, you might want to go on to the more difficult Twentieth Century Pleasures. But no one makes me laugh as reliably as William Logan, and that’s worth a lot in this world of woe.

If you’re looking for biting wit, for someone who can pierce the veil of pretentious obfuscation poets so often draw about themselves, a pint of Wm. Logan is your only man. I’d rather be skewered by him, and have my eyes opened to what’s flabby and phony in my work than be praised by a thousand fans. But I wouldn’t have fired my friend as secretary to our class, either.

[1] From “Verse Chronicle,” The New Criterion, June 2009

This morning, Larry was reading Greg Mankiw’s NY Times editorial on 45’s tax plan. Mankiw is an economics professor at Harvard. To familiarize me with Mankiw, Larry played a country western economics song, Dual Mandate for me. I guess he was directed to this from reading Mankiw, and I incorrectly reported it as Greg. An alert reader (thanks, Dan) caught the error, but the video is still worth

This morning, Larry was reading Greg Mankiw’s NY Times editorial on 45’s tax plan. Mankiw is an economics professor at Harvard. To familiarize me with Mankiw, Larry played a country western economics song, Dual Mandate for me. I guess he was directed to this from reading Mankiw, and I incorrectly reported it as Greg. An alert reader (thanks, Dan) caught the error, but the video is still worth