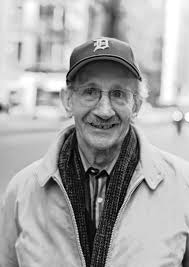

This morning I was chatting with friends about poetry over tea and muffins. We were talking about workshops, etc. I told them about my worst workshop experience, one with Mark Doty at the Walt Whitman Birthplace. Despite the awful workshop, his work is luminous. We talked about how you can’t equate the work with the person. This came home to me years ago, watching a poet I know who wrote stunning love poems to his wife and treated her like the dirt under his shoe soles.

In any case, Marcia, here’s a Mark Doty excerpt for you. Other poems of his I love include: A Green Crab’s Shell, Apparition; A New Dog; The Embrace, Migratory, A Display of Mackerel. There’s a transcendental strain in his work that he weaves in with such skill. I find it extraordinarily moving. You can find several of these at poets.org, and hear him read. He’s a good reader. Fire to Fire, his new and selected poems, is worth owning, and I even like his blog.

from “Atlantis”

I thought your illness a kind of solvent

dissolving the future a little at a time;

I didn’t understand what’s to come

was always just a glimmer

up ahead, veiled like the marsh

gone under its tidal sheet

of mildly rippled aluminum.

What these salt distances were

is also where they’re going:

from blankly silvered span

toward specificity: the curve

of certain brave islands of grass,

temporary shoulder-wide rivers

where herons ply their twin trades

of study and desire. I’ve seen

two white emissaries unfold

like heaven’s linen, untouched,

enormous, a fluid exhalation. Early spring,

too cold yet for green, too early

for the tumble and wrack of last season

to be anything but promise,

but there in the air was the triumph

of all flowering, the soul

lifted up, if we could still believe

in the soul, after so much diminishment…

Breath from the unpromising waters,

up, across the pond and the two-lane highway,

pure purpose, over the dune,

gone. Tomorrow’s unreadable

as this shining acreage;

the future’s nothing

but this moment’s gleaming rim.

Now the tide’s begun

its clockwork turn, pouring,

in the day’s hourglass,

toward the other side of the world,

and our dependable marsh reappears

—emptied of that scratched and angular grace

that spirited the ether, lessened,

but here. And our ongoingness,

what there’ll be of us? Look,

love, the lost world

rising from the waters again:

another continent, where it always was,

emerging from the half light,

drenched, unchanged.

Mark Doty

A Theory of Prosody

A Theory of Prosody