As a child, I was always looking for the door at the back of the wardrobe to get into another world. I believed that I could be transported to Narnia if I just knew where to find the door. As an adult, the poetry workshop at Squaw Valley has been the closest to that magical world for me. I first went in 1986. It was a very small gathering then, perhaps 30 or 40 poets, divided into three workshops each day, taught by Bob Hass, Sharon Olds, and Galway Kinnell.

As a child, I was always looking for the door at the back of the wardrobe to get into another world. I believed that I could be transported to Narnia if I just knew where to find the door. As an adult, the poetry workshop at Squaw Valley has been the closest to that magical world for me. I first went in 1986. It was a very small gathering then, perhaps 30 or 40 poets, divided into three workshops each day, taught by Bob Hass, Sharon Olds, and Galway Kinnell.  Galway was the Director until a year or two ago, and his generous spirit shaped the experience (a spirit Bob Hass continues to manifest).

Galway was the Director until a year or two ago, and his generous spirit shaped the experience (a spirit Bob Hass continues to manifest).

With four children and a demanding job, I hadn’t written a poem in years, and the first evening I discovered we were to write a poem that night, and read it in a workshop the next morning. The terror I felt was probably what I’d feel standing at the open door of a plane for my first parachute jump. But somehow, poetry was waiting patiently for me, and that week the poems kept coming, one after another.

The process at Squaw is simple: everyone, including the “staff poets” writes a new poem each day and reads it in the morning workshop. After each poet reads, someone jumps in and says something about what works in the poem for them. A brief discussion follows, with no criticism unless the poet asks for specific feedback on something. At first I thought, “How dumb to only say nice things.” And Dean Young, who has been a staff poet, sometimes refers to it as the “petting zoo.”

The process at Squaw is simple: everyone, including the “staff poets” writes a new poem each day and reads it in the morning workshop. After each poet reads, someone jumps in and says something about what works in the poem for them. A brief discussion follows, with no criticism unless the poet asks for specific feedback on something. At first I thought, “How dumb to only say nice things.” And Dean Young, who has been a staff poet, sometimes refers to it as the “petting zoo.”

But these poems are fresh, and we don’t know each other’s work. Pointing out what is working in the poem does several things. It focuses the writers on their strengths. It encourages them to can keep moving in that direction. There really is no need to say what’s wrong; the focus on what’s working implies what isn’t. And poetry is so much a matter of personal taste–different things move different people. As Lucille Clifton, another staff poet, often quoted, “the house of poetry has many rooms.”

Most of all, though, the spirit of the workshop encourages experimentation. Writers feel safe. No one presumes to “teach” you how to write a poem. Instead, everyone is trying hard to do their best work. Of course we each want to impress everyone with our skill, that’s a given. But over the week, everyone’s work improves.

Most of all, though, the spirit of the workshop encourages experimentation. Writers feel safe. No one presumes to “teach” you how to write a poem. Instead, everyone is trying hard to do their best work. Of course we each want to impress everyone with our skill, that’s a given. But over the week, everyone’s work improves.

It’s thrilling to watch and to experience. It’s like living in a poem. Everything informs the process. The place itself is part of the magic, but most of it has to do with the indefinable nature of community–a temporary community, to be sure–but one that makes so much possible.

I’ve been back several times. This year, while I didn’t attend, I went for the final evening, an amazing dinner at the home of Barbara Hall. Oakley Hall was one of the founding forces of this program (there are fiction and screen-writing sessions, too, although these are managed differently). The Hall family, especially Brett Hall Jones, make the ongoing workshops a reality. After dinner, anyone who wants recites a poem from memory. Sometimes, with a familiar poem like Jaberwocky or Lake Isle of Innisfree, many poets join in. I love this experience. It seems to me like watching the living voice of poetry jump from throat to throat, sometimes in different languages, always with a different voice. So that’s where I’ve been.

As a bonus, I got to hear Bob Hass talk about prosody. Someone had asked what role rhyme, meter and form play in poetry, and Bob’s answer was essentially that poetry is made of what you know. The more widely you read, the more is available to you. If you are moved by a poem, you might explore it, analyze it to see how it’s done. He had a handout that started with a line from an Irving Berlin song that haunted him:

As a bonus, I got to hear Bob Hass talk about prosody. Someone had asked what role rhyme, meter and form play in poetry, and Bob’s answer was essentially that poetry is made of what you know. The more widely you read, the more is available to you. If you are moved by a poem, you might explore it, analyze it to see how it’s done. He had a handout that started with a line from an Irving Berlin song that haunted him:

What’ll I do when you are far away?

When I am blue, what’ll I do?

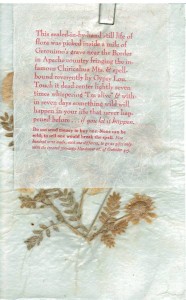

He talked about the stresses in the phrase “What’ll I do,” a stressed syllable followed by two unstressed ones, then a final stress. This pattern is called a cradle, as the two stressed syllables “hold” the unstressed ones. It’s shape goes a long way to the power of these song lines. If any of you want my notes, and the full handout, leave me a comment, and I’ll send them your way. Or you might want to hear Bob read one of my favorites of his poems.

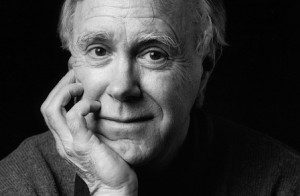

This past week was the week of the poetry workshop at Squaw Valley, and here at my house, a poetry weekend following that format. It was a wonderful weekend. I’m sure I’ll be posting something from the weekend soon–the work was exhilarating. Meanwhile, here’s a poem from a poet who has been part of the staff at Squaw Valley in years past:

This past week was the week of the poetry workshop at Squaw Valley, and here at my house, a poetry weekend following that format. It was a wonderful weekend. I’m sure I’ll be posting something from the weekend soon–the work was exhilarating. Meanwhile, here’s a poem from a poet who has been part of the staff at Squaw Valley in years past: