Even though I have been unsuccessful in my efforts to find and pick enough blackberries for jam, or even a pie, I have gathered five of my favorite blackberry poems, each somewhat characteristic of its author.

First is Sylvia Plath, whose vision of blackberries is personal–a blood sisterhood, dark, menacing full of hooks:

First is Sylvia Plath, whose vision of blackberries is personal–a blood sisterhood, dark, menacing full of hooks:

Blackberrying

Nobody in the lane, and nothing, nothing but blackberries,

Blackberries on either side, though on the right mainly,

A blackberry alley, going down in hooks, and a sea

Somewhere at the end of it, heaving. Blackberries

Big as the ball of my thumb, and dumb as eyes

Ebon in the hedges, fat

With blue-red juices. These they squander on my fingers.

I had not asked for such a blood sisterhood; they must love me.

They accommodate themselves to my milk bottle, flattening their sides.

Overhead go the choughs in black, cacophonous flocks —

Bits of burnt paper wheeling in a blown sky.

Theirs is the only voice, protesting, protesting.

I do not think the sea will appear at all.

The high, green meadows are glowing, as if lit from within.

I come to one bush of berries so ripe it is a bush of flies,

Hanging their bluegreen bellies and their wing panes in a Chinese screen.

The honey-feast of the berries has stunned them; they believe in heaven.

One more hook, and the berries and bushes end.

The only thing to come now is the sea.

From between two hills a sudden wind funnels at me,

Slapping its phantom laundry in my face.

These hills are too green and sweet to have tasted salt.

I follow the sheep path between them. A last hook brings me

To the hills’ northern face, and the face is orange rock

That looks out on nothing, nothing but a great space

Of white and pewter lights, and a din like silversmiths

Beating and beating at an intractable metal.

Sylvia Plath

Seamus Heaney’s poem focuses on the rot at the heart of the sweetness–a metaphor for Irish politics, or just a childhood memory? Either way, a disturbing poem from the glossy purple clot of the berry to the rat-grey fur of the mold:

Blackberry-Picking

Late August, given heavy rain and sun

For a full week, the blackberries would ripen.

At first, just one, a glossy purple clot

Among others, red, green, hard as a knot.

You ate that first one and its flesh was sweet

Like thickened wine: summer’s blood was in it

Leaving stains upon the tongue and lust for

Picking. Then red ones inked up and that hunger

Sent us out with milk cans, pea tins, jam-pots

Where briars scratched and wet grass bleached our boots.

Round hayfields, cornfields and potato-drills

We trekked and picked until the cans were full

Until the tinkling bottom had been covered

With green ones, and on top big dark blobs burned

Like a plate of eyes. Our hands were peppered

With thorn pricks, our palms sticky as Bluebeard’s.

We hoarded the fresh berries in the byre.

But when the bath was filled we found a fur,

A rat-grey fungus, glutting on our cache.

The juice was stinking too. Once off the bush

The fruit fermented, the sweet flesh would turn sour.

I always felt like crying. It wasn’t fair

That all the lovely canfuls smelt of rot.

Each year I hoped they’d keep, knew they would not.

Seamus Heaney

Mary Oliver’s is pure transcendence, with a thick paw of self reaching for more:

August

When the blackberries hang

swollen in the woods, in the brambles

nobody owns, I spend

all day among the high

branches, reaching

my ripped arms, thinking

of nothing, cramming

the black honey of summer

into my mouth; all day my body

accepts what it is. In the dark

creeks that run by there is

this thick paw of my life darting among

the black bells, the leaves; there is

this happy tongue.

Mary Oliver

For Bob Hass, the blackberry evokes so much else: loss, longing, love, tenderness, metaphysics. His thought reaches out like intractable blackberry vines, covering all available ground, coming to rest with the vibrant specific fruit. I especially love the line “a word is elegy to what it signifies” and the image of the “thin wire of grief” in a friend’s voice. There is so much to admire in the journey this poem makes between the meditative and the specific:

Meditation at Lagunitas

All the new thinking is about loss.

In this it resembles all the old thinking.

The idea, for example, that each particular erases

the luminous clarity of a general idea. That the clown-

faced woodpecker probing the dead trunk

of that black birch is, by his presence,

some tragic falling off from a first world

of undivided light. Or the notion that,

because there is in this world no one thing

to which the bramble of blackberry corresponds,

a word is elegy to what it signifies.

We talked about it late last night and in the voice

of my friend, there was a thin wire of grief, a tone

almost querulous. After a while I understood that,

talking this way, everything dissolves: justice,

pine, hair, woman, you and I. There was a woman

I made love to and I remembered how, holding

her small shoulders in my hands sometimes,

I felt a violent wonder at her presence

like a thirst for salt, for my childhood river

with its island willows, silly music from the pleasure boat,

muddy places where we caught the little orange–silver fish

called pumpkinseed. It hardly had to do with her.

Longing, we say, because desire is full

of endless distances. I must have been the same to her.

But I remember so much, the way her hands dismantled bread,

the thing her father said that hurt her, what

she dreamed. There are moments when the body is as numinous

as words, days that are the good flesh continuing.

Such tenderness, those afternoons and evenings,

saying blackberry, blackberry, blackberry.

Robert Hass

And finally, Galway Kinnell’s inimitable voice, squinching the joy from the fruit onto our tongues:

Blackberry Eating

I love to go out in late September

among the fat, overripe, icy, black blackberries

to eat blackberries for breakfast,

the stalks very prickly, a penalty

they earn for knowing the black art

of blackberry-making; and as I stand among them

lifting the stalks to my mouth, the ripest berries

fall almost unbidden to my tongue,

as words sometimes do, certain peculiar words

like strengths or squinched,

many-lettered, one-syllabled lumps,

which I squeeze, squinch open, and splurge well

in the silent, startled, icy, black language

of blackberry-eating in late September.

Galway Kinnell

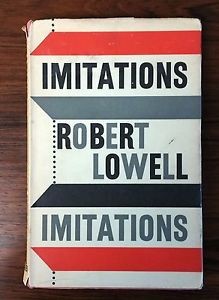

I’ve been reading some essays by C.K. Williams (who wrote last week’s poem). In one essay he talks about reading a book by Robert Lowell, Imitations, which broke open a new way of thinking about poetry.

I’ve been reading some essays by C.K. Williams (who wrote last week’s poem). In one essay he talks about reading a book by Robert Lowell, Imitations, which broke open a new way of thinking about poetry.