There are so many new poets, sometimes it’s hard to remember how many good poets have come and gone! Here’s Bert Meyer’s homage to a wonderful allium.

The Garlic

The Garlic

Rabbi of condiments,

whose breath is a verb,

wearing a thin beard

and a white robe;

you who are pale and small

and shaped like a fist,

a synagogue,

bless our bitterness,

transcend the kitchen

to sweeten death—

our wax in the flame

and our seed in the bread.

Now, my parents pray,

my grandfather sits,

my uncles fill

my mouth with ashes.

Bert Meyers, “The Garlic” from In a Dybbuk’s Raincoat: Collected Poems.

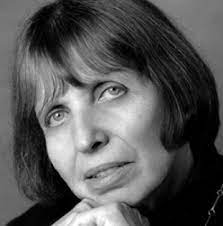

Linda Pastan died in January this year, and this seems an appropriate poem to post for her. She was born in 1932 and went to Radcliffe. During her senior year, Pastan won a collegiate poetry prize sponsored by Mademoiselle magazinem a contest in which Sylvia Plath placed second. I wonder how that felt later on.

Linda Pastan died in January this year, and this seems an appropriate poem to post for her. She was born in 1932 and went to Radcliffe. During her senior year, Pastan won a collegiate poetry prize sponsored by Mademoiselle magazinem a contest in which Sylvia Plath placed second. I wonder how that felt later on. Clouds drive westward.

Clouds drive westward. The Wall

The Wall